Documenting a life: Q&A with UIC’s Elizabeth Todd-Breland

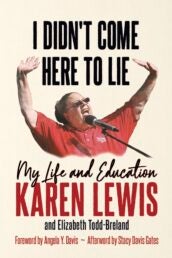

UIC history professor Elizabeth Todd-Breland’s conversations with Chicago labor leader Karen Lewis helped drive some of Todd-Breland’s research and teaching in her classes. Todd-Breland worked with Lewis as a co-author of Lewis’ memoir, “I Didn’t Come Here to Lie.”

By the time of Lewis’ death in 2021, Todd-Breland, editor Jill Petty and Lewis had recorded hours of conversations for the book, published today. These included stories of Lewis’ Chicago childhood, life in Oklahoma and Barbados and early career as a teacher. To ensure the memoir wasn’t left unpublished, Todd-Breland used speeches, writings and other first-person works by Lewis to fully document Lewis’ life in the book.

Todd-Breland’s work with Lewis on “I Didn’t Come Here to Lie” aligned with her university research on urban and social history, African American history and the history of education. And, she said, the causes that drove Lewis remain relevant.

“This is an extremely important book for the time that we are living through right now,” Todd-Breland said. “Many of the things that Karen Lewis was fighting against and fighting for are still very present in our discourse, politics and policy today.”

Todd-Breland talked to UIC today about how her relationship with Lewis and her work on the book drive her current research. This interview has been edited for length.

What did you learn about Lewis that surprised you or drove the narrative in a particular direction?

Her life was such an amazing journey of exploration. She talks about her time living in Barbados, how she actually was in medical school here at UIC for a brief period of time before figuring out, no, actually, this is not what I want to do with my life and finding teaching as her calling and passion. She made interesting connections between her journey to teaching and her journey through her religious faith. I think just the sense of exploration, the sense of curiosity that drove her throughout her life, is something that was really inspiring.

How did meeting with and working with Lewis shape your research over the last decade?

I write a lot about the history of public education and about the history of teachers, particularly Black teachers and teachers of color. Being in an extended period of communication with a master teacher — Karen Lewis taught for over 20 years, so she was a veteran Black educator — to be in conversation with her throughout the course of my own research on these topics was very formative for me.

Talking to her gave me really important perspective on big shifts in public policy and education policy over time, like the shifts towards privatization and what it looked like fighting against that on the ground.

You are often called on to develop curricula on African American history and urban education. How has Lewis’ legacy influenced how we teach and talk about urban education?

If you look at the movement that she was a part of and a leader in, to transform the conversation about public education in this country during the 2010s, it has dramatically shaped conversations about public education, not just here in Chicago, but nationally.

The demands, even if still unmet, for fully funded, well-resourced public education for all children, particularly children living in poverty, particularly children of color, is something that is a part of her legacy. In my own research into those areas, she is an important part of that story.

She aggressively pushed back against billionaires and fought for working people. She passionately and assertively defended students, teachers and public education as a whole and the importance of public education. She fought for and helped create solidarity across lines of difference that I think we can learn a lot from today. So I actually think that her words are really important for thinking about how we move forward, survive and thrive in our current moment.

How did your work on the Chicago Board of Education shape some of your discussions during the book research?

As a historian, I care a lot about “How did we get here?” So being in dialogue with someone like Karen, who was a leader in how we got to the point that we were in when I stepped into the school board role in 2019, was really important for me to think further through the “How did we get here?” And then, importantly, how do we move forward from where we are? Working on the book inspired me and helped to keep me grounded during my time on the board.

What projects are you working on now?

My main goal right now is to get Karen’s story out into the world. I’ve also been working with the Chicago Torture Justice Memorials organization on an oral history project that’s also been a long time coming. The project compiles the oral histories of survivors of police torture and their family members, so I’m working with survivors in that effort.

Additionally, I’ve been working on a project here at UIC that is part of a national project called The Renewal Project that looks at the history and ongoing legacy of urban renewal and the relationship between urban renewal and universities.

Our campus here, what was Circle and now is our Chicago campus, was a campus built as an urban renewal project. So better understanding that history and coming to terms with its legacy has been fun because I’ve been able to pursue it as a scholarly research project and through my teaching. Teaching classes about this topic, working with students on this topic and having them really be on the ground, doing research and learning from community members and community-based organizations for that project has been a lot of fun.