For the School of Theatre & Music, the show must go on, even during a pandemic

As the COVID-19 pandemic pushed classes and most of the campus online at the University of Illinois Chicago, UIC’s School of Theatre & Music pivoted to meet the challenge of presenting acting and music instruction — by their nature communal — by providing in-person, virtual and hybrid instruction.

The music and theatre departments designed formats that would utilize technology, planning and even spontaneity to provide students with the best possible instruction.

Jessica Fisch, an adjunct lecturer at UIC, worked with students and technical staff for weeks to create a filmed theatrical experience called Reverb (uicreverb.org). The piece, which also kicked off the current theatre season, had been in development since May. When COVID-19 showed no signs of letting up, the decision was made to switch from an in-person performance to an online experience.

The piece is comprised of a series of short videos that present various viewpoints of the chaotic summer of 2020. Each of the pieces was written by a UIC alumni writer and featured UIC actors and designs by UIC students, faculty and visiting guest artists, said Fisch. The pieces were made following COVID protocols and were either filmed socially distanced on location throughout the city or by the actors themselves in their homes, Fisch said.

All the artists involved were learning to use new technologies and to experiment with ways existing technology could be manipulated differently in these unique circumstances, she added.

“In some instances, this involved teaching students to use all kinds of new technologies remotely while myself and other guest artists were on Zoom talking them through it remotely,” Fisch said. “I like to think of this very large project as an experiment in what is and isn’t possible in this challenging moment.”

To create the piece, Fisch pointed to several examples from the project that demonstrated how technology not typically used in the theater was employed for the project.

- A video designer filmed a number of the pieces using a drone so that they could capture large-scale moments from a safe distance.

- The production team put together “home kits” for actors who needed to film their pieces from the safety of their home. These kits included film, lighting and sound equipment, which guest artists taught actors how to use via Zoom.

- The lighting designer created lighting using floodlights, desk lamps and ring lights among others to create theatrical spaces in non-traditional environments. She then directed the students on how to set up and use this equipment over Zoom.

- Students were taught by faculty and guest artists how to handle professional film equipment on location and a number of the pieces were filmed entirely by UIC students.

- Audio recordings were done using a technology call Zencastr, typically the domain of podcasters and radio producers. This program allowed students to record their scenes together from the safety of their homes and enabled the sound designer to isolate their unique voice tracks to be paired with filmed pieces.

- The entire production team did an overnight, remote film shoot with two students who are roommates who filmed a short horror piece in their apartment. A director, choreographer, lighting designer, costume designer, video designer, props designer and others walked the students through creating the piece over Zoom.

- One actor filmed a scene on location while her scene partner was on her phone playing the scene with her.

“Creating REVERB required an immense amount of creative thinking and re-imaging of practices,” Fisch said. “Some things just could never be re-created, including the impossibility of having actors appear close together or perform things communally.”

Fisch said Zoom was “a blessing and a curse” because while it enabled them to connect and work with the students remotely, it also brought up many challenging sound issues. For example, Zoom prevents two people from talking simultaneously and actors were frequently cut off. In addition, issues involving unstable internet connections and students not having access to reliable personal computers also came up.

“We were also asking students to perform work they would normally do in a theatre, in their homes,” she said. “Which meant navigating shared spaces and the cooperation of parents and roommates. Creating theatre requires space and all the students graciously made their private spaces public to create the work.”

In the music departments, technology also brought unique challenges to instruction.

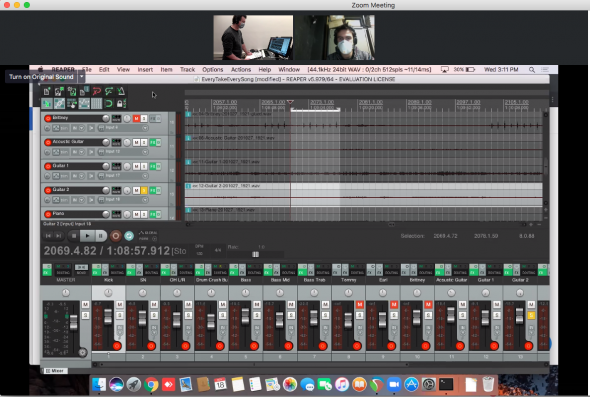

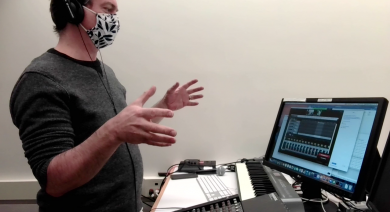

Ryan Ingebritsen, instructional laboratory specialist in the School of Theatre and Music, worked with music instructors to make technology available. The strategy was to provide students with a range of learning opportunities, including hybrid, virtual or in-person formats.

Most classes, such as music theory and music history, were fully remote with the exception of first-semester ear training, which was taught in a hybrid fashion. Some ensembles also went fully remote, including Jazz Ensemble and Choir. The ensembles used remote recording using high-quality USB microphones to record against backing tracks and videos of the director conducting, said Ingebritsen, who served as an advisor and assisted with sound mixing.

Other ensembles remained in-person but were socially distanced. Ingebritsen and his team of student workers set up a PA system in a lecture center that allowed singers in the Pop Rock and Jazz Workshop ensembles to hear themselves in the back of the large room with monitors on stage so the band also could hear, he said. The mixture of the audio was then fed into Zoom so students who were remote could also hear the high-quality sound.

In the music building, Ingebritsen and others installed an AV link system in two rehearsal halls so that players in one room could play along simultaneously as the conductor was projected on a large screen and an audio feed from the other room supplied audio. Finally, they also created a “practice and lesson studio” for the vocal jazz majors so that the sound from their microphones, as well as the room, could be heard by the teacher and they could hear the teacher through speakers.

“It requires lots of equipment to make this a balanced and natural sound,” Ingebritsen said. “It is very important for jazz and pop singers to hear their own voice through speakers and a microphone and for the teacher to be able to hear the sound they are actually making in the room.”

There was a high learning curve for students and faculty when it came to remote learning. At the beginning of the semester, The School of Theatre and Music focused on making sure that every student and faculty had the gear they needed at home, and they knew how to utilize it and connect to classes. Even students attending in-person classes students learned far more sophisticated setups than they were used to.

When it came to music instruction, remote performances proved to be more difficult than in-person performances because nuance — such as spatial reflections of sound bouncing off walls as well as haptic vibration and visual cues — is lost. Asynchronous recording projects helped to overcome many of these issues. In addition, he worked with professors to develop strategies to give students an alternate way to coordinate, including using verbal count-offs and relying more on the direct aural sense, such as listening to a specific instrument, to help with timing rather than just relying on the visual cue of the conductor.

“We are fortunate to have a very tenacious and technically savvy roster of instructors who have really risen to the challenge of both fully remote learning and hybrid teaching,” Ingebritsen said. “They are working hard to really understand how the tools available to us now can allow a different form of instruction to happen.”

Zac Boehm, a senior majoring in music who took four music-related classes including Pop Rock Ensemble, worked with Ingebritsen to set up televisions, microphones, interfaces and other technology to make sure students on Zoom could interact seamlessly with professors and classmates during hybrid sessions. Before each in-person class, he checked in with professors to make sure there were no technical glitches and that everything was clean and students were properly spaced apart.

“This allowed all music students safe and comfortable access to classes so that their education was not sharply inhibited by the severity of the pandemic,” Boehm said. “Despite the state our country and state are currently in (because of COVID), our school did a great job and I believe we exceeded all general expectations by following all the necessary and recommended guidelines.”

Categories

Campus, Faculty, Students, Uncategorized

Topics

CADA, Circle Back to Campus, COVID-19, elearning, School of Theatre & Music, technology