Physicists celebrate Nobel Prize to Higgs boson scientists

UIC physicists joined others around the world Tuesday in celebrating the announcement of the Nobel Prize awarded to Peter Higgs and Francois Englert for their work on the Higgs boson discovery.

“It is an exciting time for those of us in high energy physics,” said Cecilia Gerber, professor and associate head of physics.

“It has been a fascinating journey and it has not come to an end.”

UIC faculty members — including Mark Adams, Richard Cavanaugh, Nikos Varelas and Gerber — played a role in finding the elusive Higgs boson, which generates mass for fundamental particles.

They are planning to join researchers from around the world Oct. 23 in Washington, D.C., to celebrate the Nobel Prize award.

“In one sense it’s a Nobel Prize to the theorists and in another sense it’s a Nobel Prize to the experiments and the field for having verified this really amazing prediction,” said Cavanaugh, associate professor of physics.

Higgs and Englert began searching for the subatomic particle in the 1960s. In 2012, they presented proof of the Higgs’ existence at CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research.

“It was one of the biggest discoveries of all time,” Varelas said, professor of physics. “It opens a new chapter in the genetic code of the universe. It’s a monumental milestone for physics.

“If the Higgs did not exist, life as we know it would not be possible.”

More than 2,000 scientists across the country are working on research related to the Higgs boson, which is essential to the workings of the universe. Without the Higgs, everything would be like free-floating particles of light that could not combine to create matter.

“We’ve finally discovered this was the origin of mass,” Cavanaugh said. “That’s such a fundamental concept that sometimes we take it for granted. These great, deep mysteries of nature, we are finally beginning to understand.”

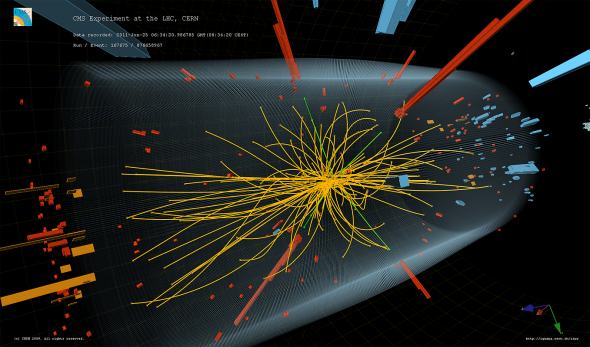

The discovery of the Higgs boson was made with help from scientists around the world, including researchers from UIC’s particle and nuclear physics group, which worked on the Compact Muon Solenoid experiment. The group analyzed LHC proton collisions for signs of fleeting Higgs particles within a mass range measured by electron volts.

“We are part of this effort, very much so,” Varelas said.

Still, there’s more work to be done, Gerber said.

“I am looking forward to the next data-taking period of the LHC starting in 2015, where I hope we will see the appearance of new physics that will force us to go beyond our current understanding of the building blocks of matter and their interactions,” she said.