2019 Alumni Awards

Six outstanding graduates were honored Oct. 24 at the Chancellor’s Alumni Awards Ceremony.

Alumni Achievement Award

Dr. Herbert Paaren, BS ’71, MS ’73, Ph.D. ’76

College of Liberal Arts and Sciences

Herb Paaren grew up in Chicago’s Hegewisch neighborhood where he spent his college summers toiling in South Side steel mills and looking for something he cherished: opportunity. Dr. Paaren found that opportunity — and firmly seized it — through his undergraduate research experience at UIC.

Although Paaren only mustered a “C” in his first semester of freshman chemistry, his passion for the science didn’t wane; in fact, it intensified during his second year in an organic chemistry course taught by Dr. Robert Moriarty, now an emeritus professor in UIC’s Department of Chemistry. Impressed with Paaren’s promise, Moriarty invited him to conduct research in his lab.

“At last! [I had] my opportunity to engage with professional research,” Paaren recalls. “I dug in.”

When that research door opened, Paaren rushed through. After completing his bachelor’s degree at UIC, he earned a master’s degree in chemistry, followed by a Ph.D., before receiving a National Institutes of Health Fellowship at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

The momentum that started as a student resulted in an entrepreneurial scientific career, highlighted by 15 patents related to his work in synthetic organic chemistry.

“When you combine some intellect and motivation with opportunity, then good things happen,” Paaren says. His research into metabolic chemistry and specialty chemicals sparked the creation of his company, Tetrionics, in 1990.

“When I got out into the real world, I learned I could punch above my weight, thanks to UIC,” he says.

In 2004, Sigma-Aldrich acquired Tetrionics, and Paaren and his wife, Denise Marino, launched an endowment at UIC’s College of Liberal Arts and Sciences to fund graduate student scholarships and summer internships for undergraduates interested in chemical sciences.

Over the past 15 years, Paaren and Marino have made supporting UIC a top priority. The couple’s Single Step Foundation — a name drawn from the Chinese proverb that states that life’s most fulfilling journeys begin with a single step — supports students’ scientific pursuits and provides funds to modernize UIC’s library. This past November, Paaren and Marino also gave UIC’s Department of Chemistry significant funds for instrumentation and, of course, student opportunity.

Paaren admires the gritty spirit of UIC’s students, noting that, “Creating an environment where students can take advantage of opportunities much like I did is a great feeling.”

— Daniel P. Smith

Dr. Kathryn Roach, BS ’74, Ph.D. ‘91

College of Applied Health Sciences and School of Public Health

Kathryn Roach views her physical therapy (PT) career as two interrelated chapters. And she is quick to credit UIC with playing an essential role in both.

In her first chapter, Roach was a clinical practitioner for 14 years, working in the burn unit of Chicago’s former Cook County Hospital and as an in-home physical therapist.

“I worked with people as they fought to regain their ability to fully participate in their lives,” Roach says. “It was an enormous honor.”

She was trained for that role in the second-ever PT class at UIC, meeting in classrooms next to what became the Library of the Health Sciences.

“We watched the construction from our classroom windows, and the workers watched us practice our clinical skills,” she recalls. “Little did I know I would spend hours in that same medical library doing dissertation work.”

In fact, Roach never imagined herself leaving clinical practice, but an interest in research led to her second chapter. She returned to the UIC School of Public Health to pursue a Ph.D. in epidemiology. There, she learned to take a broader view of health and illness, and explored possibilities in preventing and treating disabilities.

“As much as I loved the first chapter of my career, I think I have loved the second chapter even more,” she says. “I went into academics to participate in clinical research, but what I did not anticipate was how much I would love teaching.” Roach is now a professor of physical therapy at the University of Miami’s Miller School of Medicine, as well as vice chair for research and acting vice chair for its Ph.D. studies.

As a clinician, Roach realized that physical therapists needed better ways to measure patients’ functional outcomes, and she helped develop a range of widely used measures, including the Physical Therapist Clinical Performance Instrument (PT-CPI), used to assess physical therapy students during their clinical internships. Because of skills she acquired during her Ph.D. work, she served as a methodologist on exercise intervention studies of patients with Alzheimer’s disease, spinal-cord injuries and lower-limb loss.

Roach has also attended to the restorative powers of giving back. She established the Donna Roach Scholarship at UIC, named for her mother’s “courage and persistence.” Although her mother’s father thought it was a waste of time and money for a woman to go to college, her mother was determined. UIC was where her parents met — both were the first in their families to graduate from college.

Roach affirms, “My parents instilled in me a belief in the value of education.”

— Julie Sevig

Distinguished Service Award

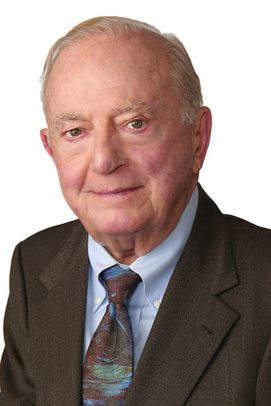

Dr. Andrew J. Haas, MS ‘57

College of Dentistry

Andy Haas has been a pioneering force in the field of orthodontics. He trained and mentored more than 600 clinicians during his 57 years of service, essentially preparing two generations of orthodontists.

“The College of Dentistry provided me with the finest education I could have possibly had, and so much of my career thereafter was about putting that great education to use to improve the industry,” says Dr. Haas, who retired this past January as a clinical professor of orthodontics at UIC.

Two factors motivated Haas to come to UIC in 1953: the premier global standing of its orthodontics graduate program, and Dr. Allan Brodie, a trailblazing force in orthodontics who passed away in 1976. In addition to leading the creation of the University’s Department of Orthodontics graduate program in 1929 — one of the earliest such efforts in the nation — Brodie developed the edgewise appliance, among the most popular orthodontic tools.

“I was his willing disciple,” Haas says of Brodie. So much so that when Haas began teaching at UIC in 1961, he led a quarterly course on Brodie’s treatment techniques that favored the biological over the mechanical. His admiration for his mentor even included naming the youngest of his five sons after Brodie.

Haas spent more than five decades diligently guiding trainees at UIC, though he also taught courses at Ohio State University, Loyola University–Chicago and Philadelphia’s Temple University. In all, Haas helped train more than 800 practitioners, a sizable number given that only 10,600 orthodontists currently practice in the U.S., according to the American Dental Association.

Beyond the University’s classrooms, Haas brought undeniable prestige to UIC and its College of Dentistry through international speaking engagements, workshops, professional affiliations and pioneering practice techniques, including his innovative work on palatal expansion. His groundbreaking 1961 paper on that technique has garnered more than 1,000 citations and is considered a classic.

“He has elevated the standards of the orthodontics specialty and influenced countless orthodontists worldwide to deliver excellence in clinical care,” says Dr. Veerasathpurush Allareddy, head of the UIC Department of Orthodontics.

Even at age 90, Haas still has a passion for orthodontics. He jumps at the chance to talk about an upcoming teaching trip to Brazil and eagerly engages in discussions about jaw development, dental practice and its innovations.

“I owe so much to the University, the education and experiences it afforded me. I have simply tried to pass that along as best I could,” Haas says.

— Daniel P. Smith

Humanitarian Award

Dr. John M. Corboy, MD ‘63

College of Medicine

As John Corboy approached his retirement in 1998, he had a vision. He looked back on his successful, decades-long career in ophthalmology and knew he wanted to do more. “I don’t think you should retire from something, but to something,” says Corboy, who had already achieved more than most.

“At every juncture, I had been favored. I believe [this is] my opportunity to pay the world back, to leave it in a better place than I found it,” Corboy says.

When he applied to UIC as a student from Hawaii, the Islands had yet to fully achieve statehood. Corboy was one of only a few international students accepted to UIC’s medical school. When his friends were drafted to serve in Vietnam, he worked with the U.S. Coast Guard’s U.S. Public Health Service in California. He later participated in an educational mission to work with underserved populations in Tonga. That experience would become the inspiration for his humanitarian efforts today.

As a student, UIC impressed upon him the importance of lifelong learning and service — ideals that continued to guide him throughout his career.

In the 20 years since his retirement, Corboy has focused on expanding the Hawaiian Eye Foundation, a not-for-profit he started in 1984 out of his own pocket. The Foundation has grown from one annual mission to 30, conducting more than 300 service trips to nearly three dozen countries. It provides care to more than 200,000 poor and blind patients in Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands, including Tonga, Myanmar, Cambodia and Vietnam.

Corboy also founded the Hawaiian Eye Center, which serves patients in that state regardless of their ability to pay, and the Royal Hawaiian Eye Meeting, the third-largest such conference in the U.S., which hosts doctors from across the globe.

A large part of Corboy’s humanitarian work involves training local surgeons in the countries he visits, equipping them with practical skills and techniques they can perform themselves. For example, to treat patients with cataracts, Corboy and his team teach a simplified procedure that requires no electricity or expensive supplies.

“When you treat someone who has never seen their grandchildren, and they point to them and say, ‘I see you. I see you. I see you,’ they burst into tears and I burst into tears. What a great gift to be able to give people,” he reflects.

“But people are going blind faster than we can treat them,” he adds. “I won’t stop doing this work until every blind and poor person is cared for.”

To that end, Corboy hopes to recruit residents and fellows in UIC’s Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences to join his team on future service trips. “If we get 52 people to give one week of their time, we’ll have an entire year covered, and that will make a huge difference to so many people,” he says.

—Jan-Henry Gray

Rising Star Leadership Award

Dr. Mulokozi Lugakingira, MS ‘11

College of Dentistry

Mulokozi Lugakingira not only reconstructs faces, he rebuilds lives. His story is so positive, it may also readjust some worldviews.

With boundless energy and vibrancy, Dr. Lugakingira, who practices oral surgery in Fort Wayne, Ind., moves effortlessly from describing his restoration of a gunshot victim’s face to his philosophy on life.

“I ask myself, ‘What have I done to change at least one life?’ Not just for my wife or kids, but for others? For 10- or 15-year-old children who get up at 4 a.m. to walk several miles to school and all they want is a book to read?”

He’s referring to his native Tanzania in East Africa, where he returns twice a year. He and his wife Kos established a nonprofit organization, Kagera Advancement Inc., to create and support a school and a clinic in his impoverished village of Katale.

The eldest of five children, Lugakingira was inspired to go into medicine by visiting his mother, a nurse, at work, and by his uncle, who told him that because there were only two oral surgeons in Tanzania, the need was great, and that work could also be his path to success.

After graduating from the University of Dar-es-salaam in Tanzania, Lugakingira was one of 15 students accepted into the only dental school in that nation. Deciding that he could get a better education in the U.S., he moved to the States in 2000 to establish residency. He was accepted into the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Dental Medicine, where he received his second dental degree. (A comparable degree is required by law in order to practice in the U.S.) While he practiced general dentistry, Lugakingira sent money home to his family in Tanzania, in part to support his siblings’ tuition costs.

Eventually, Lugakingira returned to his dream of becoming an oral surgeon. He interviewed with 15 oral and maxillofacial surgery programs and was delighted to receive an offer from his first choice: UIC. He could get hands-on experience with everything that interested him, including trauma, orthognathic surgery and dental implantology.

He joined UIC’s Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery as an intern in 2006, became a resident a year later and eventually was named one of two chief residents. With the goal to practice in the U.S. and Tanzania, he entered UIC’s master’s program in oral sciences in 2008, the first student to pursue both degrees simultaneously. Lugakingira recalls to this day, the rigor of returning to his fifth-floor room after a day of residency, peering into a microscope until well past 11 p.m. and having to report for rounds again at 5 a.m.

Lugakingira says he attained success by simply following his father’s wisdom: Education is the No. 1 weapon you can use; health is the No. 1 gift you can give.

“I do everything that I dreamed to do,” he says. “My goal is to inspire those who are disadvantaged to believe they can keep pursuing their dreams.”

— Julie Sevig

Bing Liu, BA ‘11

College of Liberal Arts and Sciences

When recommending cinematographer and filmmaker Bing Liu for a UIC Alumni Award, David Schaafsma, UIC professor of English and director of English education, joked that he was glad he failed to convince Liu to become an English teacher.

Instead, Liu’s talents are being showcased on the screen. His film, Minding the Gap, was nominated for Best Documentary at this past year’s Academy Awards. With skateboarding footage and interviews gathered over 12 years, the documentary follows the lives of three Rockford skateboarders — Liu and two others.

A.O. Scott wrote in The New York Times, “With infinite sensitivity, Mr. Liu delves into some of the most painful and intimate details of his friends’ lives and his own, and then layers his observations into a rich, devastating essay on race, class and manhood.”

Liu, who got his first camera at age 14, has worked steadily as a director and cinematographer on various films and television shows since graduating from UIC. He began by working on camera crews, worked on his first major film (At Any Price) in 2013, and was in his early 20s when he decided to make Minding the Gap. He is both humbled and honored to accept his recent recognition. “That’s not to say I don’t still struggle with feeling awkward about owning celebratory moments,” Liu admits.

“I certainly didn’t know when I started at UIC that I’d be immersing myself in one of the top English departments in the country. I didn’t even know what my major was going to be. The Asian American Literature classes made me grapple with my identity. And the Mandarin classes reawakened a language that I was once fluent in,” he says.

Liu returned to campus earlier this year as a guest speaker and workshop leader. “It felt great to be able to come back and revisit and see a younger version of myself in all those students hunkered down in the library, walking around campus and engaging in thoughtful conversation,” Liu says.

Helen Jun, UIC associate professor of English and African

American studies, notes that Liu stands out not only for his talent but also

for his demeanor. She and other faculty from the Global Asian Studies program

often attended local film festivals to support him, even before

his talents led to fame.

Liu’s next project, Until the Lion Speaks, looks at Chicago gun violence. The challenge, Liu says, is to keep people from tuning out as soon as they hear about the topic.

“I think that’s the challenge to artists: to get people to take a second look at something and reimagine it in a way that can inspire change,” he says.

— Julie Sevig