Chicago’s first hospice donates papers to UIC: ‘We existed for our patients and families’

Several dozen people who had worked at or been impacted by the first hospice to open in Chicago were at the University of Illinois at Chicago recently to celebrate the role that Horizon Hospice played for hundreds of people and their families for more than 40 years.

In 1978, Horizon Hospice became Chicago’s first hospice when it admitted its first patient. Just a decade later, Horizon was serving 109 patients annually by the time the HIV/AIDS crisis was taking its toll, and it continued growing to about 2,000 patients by 2013, regardless of their ability to pay. In 2015, it merged with two suburban hospices to form JourneyCare Hospice and Palliative Care.

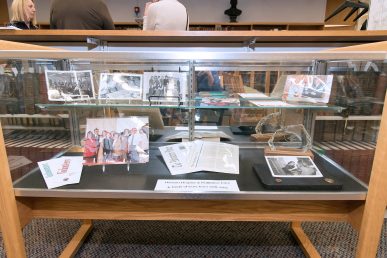

To celebrate the role Horizon Hospice played in the city and to share its history with researchers, officials have donated its archives to the University of Illinois at Chicago, which will house them in the Library of the Health Sciences-Chicago Special Collections and University Archives.

University Librarian and Dean of Libraries Mary Case thanked hospice founders for entrusting their archives to UIC. The collection was processed by Special Collections librarian Megan Keller Young and students Lauren Janik and Maria Vargas.

“Collections like this are a treasure trove for researchers investigating the story of care of the underserved and marginalized communities in our city, among many other topics,” Case said.

Dr. Michael Preodor, the hospice’s first medical director, recalled how everyone from the board of directors down to the volunteers and office workers believed that their focus was on — and should be on — the patients and their families.

“We remained committed to treating suffering from any cause, physical, psychological, social or spiritual and to help them find peace and meaning in their lives,” said Preodor. “[We] never lost sight of the fact that we existed for our patients and families.”

In addition to being the first hospice in Chicago, Horizon Hospice helped found the Illinois State Hospice Organization, which helped pass the Illinois Hospice Licensing Law in 1983.

AIDS patients were a particular focus for the hospice, and in 1992, it partnered with Chicago House, a residential center that provided patients with end-of-life care. Another focus for the hospice was children, which led to the formation in 2004 of “All About Kids,” its pediatric hospice and palliative care program. Bereavement assistance was essential to its services for families, and its “BraveHeart” program served grieving children in schools in underserved neighborhoods.

“Horizon Hospice took a philosophy of care for the dying and used it to help all,” Preodor said. “When we and the world were ambushed by the epidemic of HIV/AIDS in the 80s and 90s, our volunteers, nurses and doctors stepped up to offer hospice to a new kind of patient, a patient unfairly isolated and stigmatized.”

The doctors and nurses worked with trained volunteers to serve the patient and the caregivers. Since they knew that death was a family affair, the involvement of the family and friends helped the survivors as much as the patients.

In 2012, the hospice established the Ada F. Addington Inpatient Hospice Unit at Rush University Medical Center, named after one of Horizon’s four founders.

“Horizon Hospice is an excellent example of how citizens can invent a better way to deliver services to the community that is more effective and less expensive,” said Joan Flanagan, a founding board member, and longtime patient care volunteer.

“Starting from a board of eight people, Horizon, with the support of smart grant makers and individual donors, could create a model for end-of-life care that was more patient-controlled and patient-oriented, could involve the entire family of caregivers so they had a better experience and greatly reduced expenses,” Flanagan said.

The Horizon Hospice records include 28 linear feet of organizational and operating records, annual reports, correspondence, photographs and demographic information, said Keller Young. She said the collection will be helpful to students, staff and non-UIC researchers with an interest in the history of palliative and hospice care in Chicago. In addition, a large portion of fundraising correspondence is available, which would be of interest to people looking into nonprofit philanthropy.

Keller Young said that as they were preparing the collection, they were stirred by the founders’ priorities as they were creating the hospice: to provide pain control, give the patient the opportunity to control the rest of their life, prevent patients from dying alone, prepare the patient’s family and the patient for end-of-life and to provide an environment so the patient may die at home if they wished.

“We are both moved by the passion and fortitude of the hospice personnel,” Keller Young said.