Heightened social pain in depression tied to pain perception

Differences in the neurochemical system that regulates physical pain may explain why social rejection hurts so badly for people with depression — and why they feel less of a glow from social acceptance.

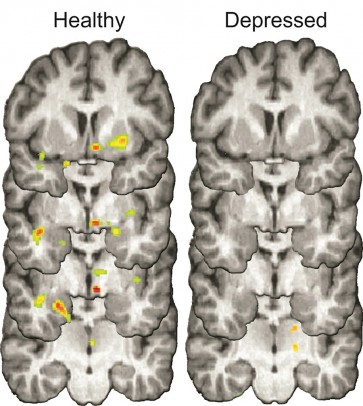

The brains of healthy individuals (left) released natural opioids during social rejection (colored spots) that may help reduce negative emotions associated with rejection. Study participants with depression (right) did not release as many opioids, which may contribute to a lingering depressed mood after rejection. Photo: David Hsu, Stony Brook University (click image to download)

The findings, reported in the journal Molecular Psychiatry, build upon previous work by researchers at the University of Illinois at Chicago; Stony Brook University; and the University of Michigan Medical School, where the study was done, that showed that pain-dimming neurochemicals, called opioids, lessen the sting of social rejection in those not suffering from depression.

“We found that opioid activity in response to rejection is altered in people with depression,” said Scott Langenecker, associate professor of psychiatry at UIC, and an author on the study. “It doesn’t mediate social pain as well as it does in non-depressed people.”

The researchers used a simulated online dating scenario — and a positron emission tomography, or PET scanner — to look at opioid activity in the brains of 17 participants diagnosed with major depressive disorder (who were not on medication) and 18 nondepressed subjects.

First, participants viewed photos and profiles of hundreds of adults and were asked to pick those they would be most interested in dating. (They were told that the profiles were made up and that no actual dates would result.)

Participants then received an injection containing a tracer compound that would bind to opioid receptors in the brain and show on the PET scan the precise location and level of opioid activity. Scans were done as participants were told whether the people whose profiles they chose either liked them back or rejected them.

PET scans of depressed participants who were told they had been rejected showed reduced opioid activity in regions of the brain that regulate stress, mood and motivation. They and the nondepressed participants alike reported feeling sad when rejected, but the depressed subjects felt sad longer.

When participants were informed that people liked them back, only nondepressed individuals showed increased opioid activity in an area of the brain called the nucleus accumbens, which is involved in positive emotions — even though all subjects reported feeling happy and accepted in these moments. Depressed participants, however, reported that their positive feelings dissipated quickly.

Scott Langenecker, UIC associate professor of psychiatry. Photo: Joshua Clark/UIC Photo Services (click image to download)

“Every day we experience positive and negative social interactions,” said lead author David Hsu, of Stony Brook University. “Our findings suggest that a depressed person’s ability to regulate emotions during these interactions is compromised, potentially because of an altered opioid system. This may be one reason for depression’s tendency to linger or return, especially in a negative social environment.”

Especially for nondepressed people, Hsu said the finding “builds on our growing understanding that the brain’s opioid system may help an individual feel better after negative social interactions, and sustain good feelings after positive social interactions.”

Langenecker said almost all subjects were enrolled in a subsequent treatment study, which should allow the researchers to learn how these opioid changes to acceptance and rejection relate to success or failure of standard treatments for depression.

“We expect work of this type to highlight different subtypes of depression,” he said, “where distinct brain systems may be affected in different ways, requiring us to measure and target these networks by developing new and innovative treatments.”

Other authors on the paper are senior author Jon-Kar Zubieta and Benjamin Sanford, Tiffany Love, Dr. Brian Mickey and Robert Koeppe of the University of Michigan; Kortni Meyers of Wayne State University; Sara Walker of the Oregon Health & Science University; and Kathleen Hazlett of Marquette University.

The research was supported by the National Institute of Health grants K01 MH085035, K23 MH074459, R01 DA022520 and R01 DA027494, and by the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation, the Rachel Upjohn Clinical Scholars program, the Michigan Institute for Clinical & Health Research, and the Phil F. Jenkins Foundation.