Rockford researcher develops vaccine for tropical disease

Rockford medical researcher Ramaswamy Kalyanasundaram spent five months in rural India studying lymphatic filariasis, a disfiguring tropical disease.

Scientists all over the world have spent decades trying to eradicate lymphatic filariasis — commonly known as elephantiasis — in developing countries.

The disease, transmitted by mosquito, causes abnormal swelling of skin and tissue of the limbs and genital area. More than 40 million people are disfigured and incapacitated by the disease, with 120 million infected and 1.23 billion in 58 countries at risk, the World Health Organization says.

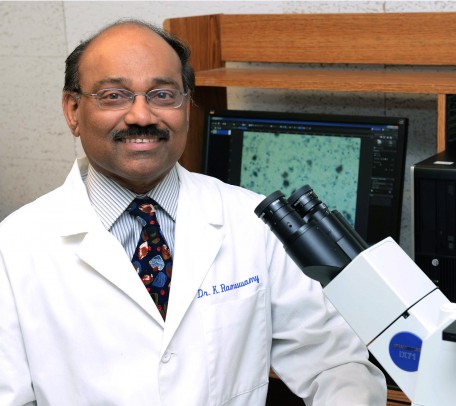

Ramaswamy Kalyanasundaram, a researcher at the College of Medicine at Rockford, has developed a vaccine that could stop the spread of the tropical disease.

Ramaswamy spent five months in rural India to gather data on lymphatic filariasis, the second-leading cause of physical disability in the world. Through a mass drug administration program spearheaded by the World Health Organization, anti-filarial medicine has been distributed to people who live in endemic regions, including India, for the past 10 years to try to stop the spread of the infection, he said.

“India has been trying to eliminate this infection so I took the opportunity to go around and get information on the current status of the infection,” said Ramaswamy, professor of microbiology and immunology, head of biomedical sciences and assistant dean for research.

His findings show that medicine alone isn’t enough. The survey results showed new infections emerging in more than 20 villages he visited, with only a small percentage of individuals immune to the infection. His team spent about six weeks collecting blood samples from villagers, with about 100 people lining up each night to provide a sample for the study.

About 10 years ago, 14 percent of villagers were infected. His survey showed that 5 percent currently have the elephantiasis.

“The infection is still there,” he said. “That means that it has not gone or is coming back.”

Ramaswamy believes that a combination of medicine to treat infected villagers plus a vaccine for those who live in endemic communities could eradicate the disease. About four years ago, he developed a vaccine that’s getting ready for clinical trial. He’s searching for funding to bring his vaccine back to India.

“Five of the villages have agreed to work with me to start the clinical trial,” he said. “We will combine that with the medicine to prove that it can eradicate the infection from a community.”

His survey work in India was funded by a Fulbright-Nehru Academic and Professional Excellence Fellowships and a Professional Excellence Scholar Award from Council International Exchange Scholars.

He collaborated on the project with the Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences, Sevagram, Maharashtra and the Regional Medical Research Center of the Indian Council of Medical Research.