UIC filled with brutalist style that inspired Oscar hopeful

Everywhere you look on UIC’s campus, you can see examples of the architectural style called brutalism. It’s evident in the raw concrete surfaces of University Hall, and the scale and masonry of the Behavioral Sciences Building. Love it or hate it, it’s a style that inspires strong reactions.

As an architectural style, it’s at the center of the Academy Award-nominated movie “The Brutalist” in which actor Adrien Brody plays a Hungarian architect who immigrates to the United States after WWII and specializes in brutalist architecture.

Related story: How a UIC professor helped “Brutalist” stars find their voices

With “The Brutalist” being a frontrunner for the upcoming Oscars, UIC today turned to David Taeyaerts, campus architect and associate vice chancellor of planning, sustainability and project management, to explain this bold style that’s all over campus. This interview has been edited for length.

Let’s start by defining brutalist architecture. What are its origins? What are its defining characteristics?

The term is derived from béton brut, which is French for “raw concrete.” … It can be traced back to buildings that were designed in the 1950s by Le Corbusier. He was a Swiss-French architect, and one of the pioneers of modern architecture.

In terms of the defining characteristics, there’s probably a handful. One is monumental in scale. … Then, exposure of the structure and building systems. So, when we talk about that – the columns, beams, ductwork, piping, and lights — all that’s exposed, rather than hidden or concealed.

Another characteristic is material authenticity, in that primarily the buildings are built in concrete. So, it’s an authentic use of that material.

Then, maybe the last one is this connection to the masonry traditions of the past. So, with the concrete, you’ll see different textures done by hand. You’ll also see a lot of brick masonry and stone in these buildings.

On the inside, there’s a lack of ornamentation. It’s very honest in terms of the architecture. Nothing’s really being concealed or hidden.

Now, that creates its own challenges. When you have all these hard materials and components exposed, sound just bounces all over the place.

What is brutalism’s place in history?

It’s part of the modernist movement in architecture that developed after World War II. If you can imagine this as a reaction to World War II, this movement disavowed the nationalism that you saw in Germany and Italy. It rejected all historic styles and favored contemporary materials and modern building technologies.

Brutalism lent itself really well to public or civic buildings, and, at the time, they were expressing this kind of collective aspiration through these big, monumental buildings. College campuses, in particular, really embraced this architectural style in the ’60s and ’70s.

As a style, brutalism elicits strong emotions. Why do people either love or hate the look?

I think it probably has to do with the fact that everybody has a different standard of beauty, right? Your standard of beauty is different from mine, and so if you encounter something that’s really different from your standard of beauty, and you don’t know why it was done that way — whether it’s art in the art museum, or whether it’s a building like a brutalist building — if you don’t understand why and have no background on it, then chances are you’re not going to like it.

But if you know a little bit about the buildings and why they were designed this different way, then people are sometimes open to changing their perception of how beautiful these buildings are.

What are the best examples of brutalism on campus, and why?

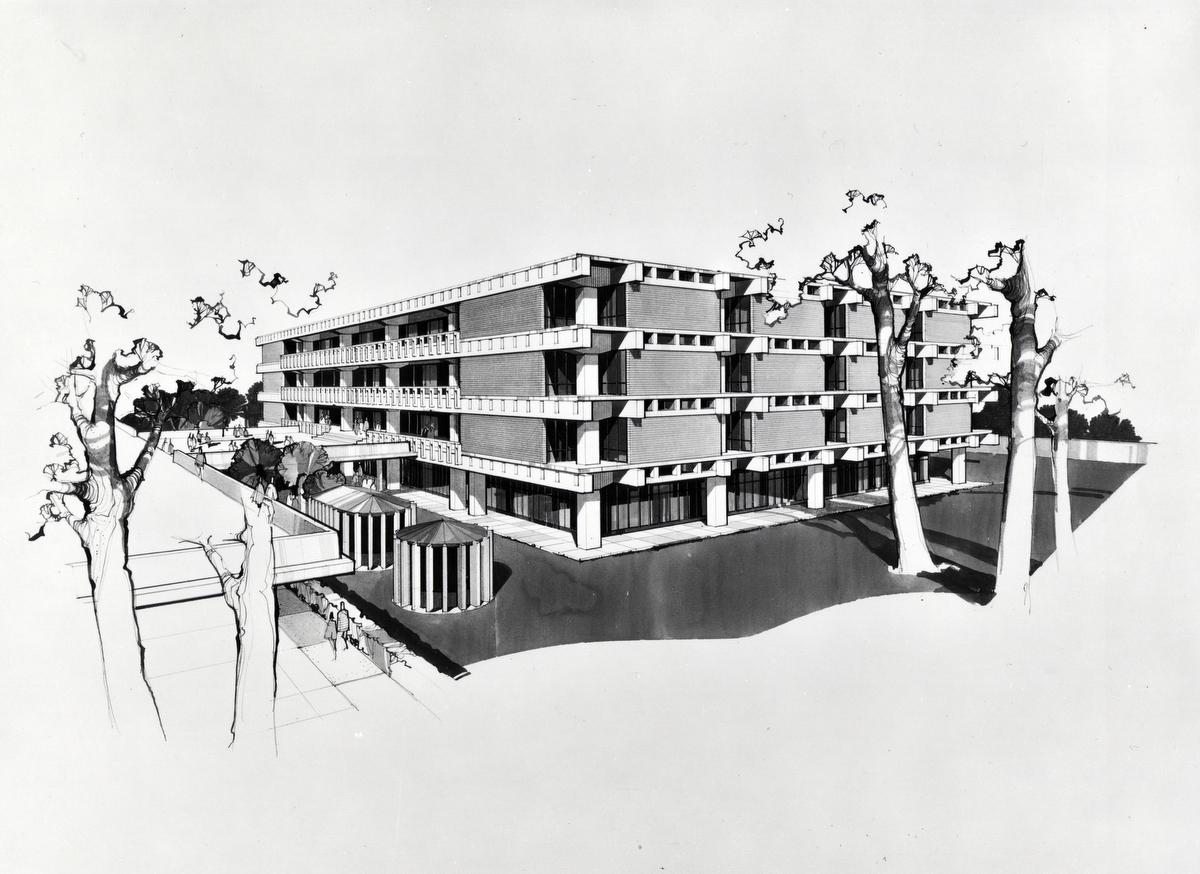

University Hall is the tallest, most visible brutalist building and it’s a campus landmark. If you’re looking at it from the east or west sides — and hopefully you’ll do this — you’ll see it’s got something called “a big shoulder” design. It actually gets wider as you go up, which is unique. It’s a great example of the exposed structure, especially on the outside, where you can read the structure really clearly. Also, the concrete has a different texture.

If you look at the columns and the beams from the outside, you’ll see this exposed aggregate; it’s rough on the surface. If you go to the north and south sides, you’ll see scored concrete in this big channel that runs up the whole length of the building. And even if you go on the inside, you’ll see what we call “board-formed concrete” that looks like you could see the individual boards that were used to make the formwork for the concrete. And that was intentional to show off the hand-crafting of it.

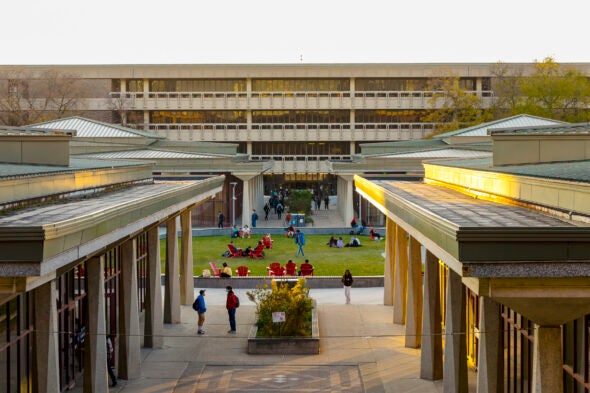

A building that is tall and monumental on a horizontal scale would be the Daley Library. If you look at it from the outside, you can see the exposed structure, the columns and the beams at each floor. There’s a lot of use of masonry, which is different from University Hall. If you go inside, you can see not just the exposed mechanical and electrical systems, but if you go into, let’s say the IDEA Commons, and you look up, you can see some beams are really massive compared to other beams. Since they’re all the same strength concrete, it’s really honest in terms of telling you which ones are carrying the most load.

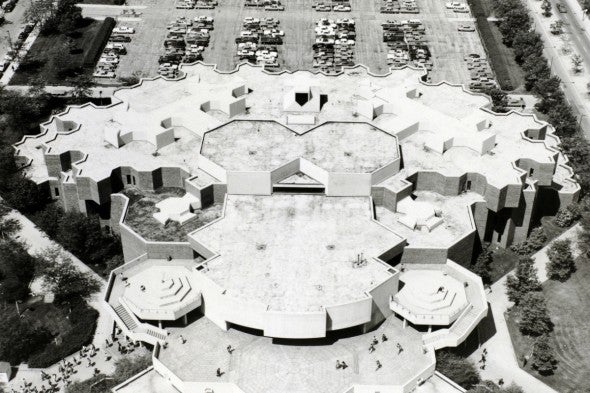

The Field Theory buildings — the Behavioral Sciences Building, the Architecture and Design Studios building and the Science and Engineering South building — are another example. Like University Hall, they are monumental in scale and illustrate masonry traditions, but they are no longer rectilinear in shape. … They tend to have more of an organic shape, but it all comes down to a simple square. The architect, Walter Netsch, used this simple square and rotated it and kept rotating it to create these very complex shapes. He called it the Field Theory. If you went to the 28th floor of University Hall and looked down on the Behavioral Sciences Building, you’ll see it has a very organic shape, almost looks like something you might encounter in nature.

Inside, there are no rectilinear rooms, and it creates these interesting public spaces in-between enclosed rooms.

What are the difficulties in updating a brutalist-style building to today’s environmental standards?

On the outside, anytime you have exposed concrete in a cold-weather environment, you’re asking for trouble. One thing is true: All concrete cracks. When it cracks, it opens up opportunities for moisture to get in. Then when water gets in and freezes and thaws, it pops out chunks of the concrete, which we call “spalling.” That exposes the rebar behind it and looks unsightly.

Making brutalist buildings energy-efficient and eco-friendly is really challenging. In all these original buildings, the glass is single-pane. If you’re in a newer house or any newer building, it’s got a minimum of double-pane glass with an air pocket in between, which provides better insulation.

In all these original UIC buildings, they also didn’t insulate the exterior walls. The precast concrete walls are hollow and have an air pocket, which helps a little bit, but not much from a thermal-transfer perspective. Trying to renovate the facades and to address those concerns is a really big challenge.

The interior spaces can feel kind of cold, and we try to warm them up by adding wood. We also tend to add patterns and colors in furniture fabrics to add a pop of visual interest/contrast.

Is brutalism making a resurgence?

I don’t think so much in terms of designing buildings in the brutalist style, but I think there’s a new appreciation. If you like to travel, you can visit a lot of well-known cities, and they have maps of their brutalist buildings. There’s one in Boston; there’s one in Washington, D.C. Even overseas, if you go to Paris, London or Sydney, Australia, they have brutalist maps. You can find these buildings because they were built all over the world.

Probably the most fun is (an Instagram account), cats of brutalism, and you’ll see images of cats in these brutalist structures. So that’s the fun of the movement.

Categories

Topics