Why is visceral fat worse than subcutaneous fat?

Researchers have long-known that visceral fat – the kind that wraps around the internal organs – is more dangerous than subcutaneous fat that lies just under the skin around the belly, thighs and rear. But how visceral fat contributes to insulin resistance and inflammation has remained unknown.

A study led by researchers at the University of Illinois at Chicago points blame at a regulatory molecule in cells called TRIP-Br2 that is produced in response to overeating’s stress on the machinery cells use to produce proteins.

The findings are published in the journal Nature Communications.

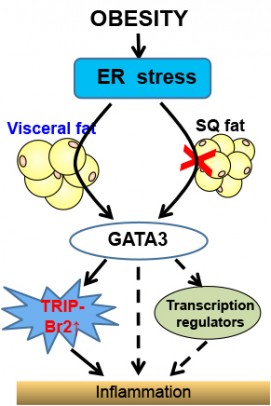

Obesity and stress on the endoplamic reticulum cause inflammation through upregulation of GATA 3 and TRIP-BR2 in visceral fat. Credit: Chong Wee Liew.

All body fat is not created equal in terms of associated health risks. Visceral fat is strongly linked to metabolic disease and insulin resistance, and an increased risk of death, even for people who have a normal body mass index. Subcutaneous fat doesn’t carry the same risks — some subcutaneous fat may even be protective.

In previous studies, Chong Wee Liew, assistant professor of physiology and biophysics in the UIC College of Medicine, and his colleagues found that in obese humans TRIP-Br2 was turned-up in visceral fat but not in subcutaneous fat. When the researchers knocked out TRIP-Br2 in mice and fed them a high-calorie, high-fat diet that would make the average rodent pack on the grams, the knockout mice stayed relatively lean and free from insulin resistance and inflammation.

“TRIP-Br2 appears to block or prevent normal lipolysis,” Liew explained. Lipolysis is the breakdown of fat in fat cells, for use as fuel, and ongoing lipolysis can prevent the buildup of excess fat in those cells, Liew said.

“Without TRIP-Br2, lipolysis and oxidative metabolism take place at an increased rate, so fat is broken down and quickly used as energy and does not have a chance to build up in organs like the liver,” he said.

But Liew and his colleagues still didn’t know why TRIP-Br2 was found in higher amounts in visceral fat than in subcutaneous fat.

Their search for answers led them to a cellular structure called the endoplasmic reticulum, or ER, which is responsible for producing all the proteins in the cell. Nutrients from a meal enter the ER, but an excess due to overeating can significantly stress it. In obesity, a stressed ER in visceral fat cells leads to production of inflammatory molecules called cytokines — but exactly how was unclear.

Liew and coworkers found that in the absence of TRIP-Br2, ER stress could no longer trigger cytokine production and inflammation in obesity. They also found that the up-regulation of TRIP-Br2 in visceral fat depends on an intermediary factor called GATA 3 that turns on TRIP-Br2.

“Together, our findings indicate that these molecular regulators, TRIP-Br2 and GATA3, could be viable targets for small drug molecules that could serve as potential therapeutic agents against obesity,” Liew said.

Co-authors on the study are Guifen Qiang, Hyerim Whang Kong and Maximilian McCann of UIC; Difeng Fand and Jinfang Zhu of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease; Xiuying Yang and Guanhua Du of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College; and Matthias Bluher of the University of Leipzig.

This research was supported in part by the Research Open Access Publishing Fund of UIC; grants K99 DK090210 and R00 DK090210 from the National Institutes of Health; a Novo Nordisk Great Lakes Science Forum Award; a RayBiotech Innovative Research Grant Award; a Center for Society for Clinical and Translational Research Early Career Development Award; UIC startup funds; and grant SFB 1052, B01 from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.