UIC scientists discover method for restoring memory loss from Alzheimer’s disease

A team of researchers at the University of Illinois Chicago has discovered a way to restore memory loss from Alzheimer’s disease in mice by boosting the production of neurons, the basic cells of the brain.

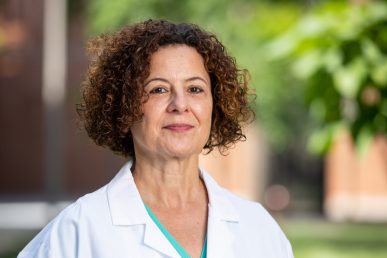

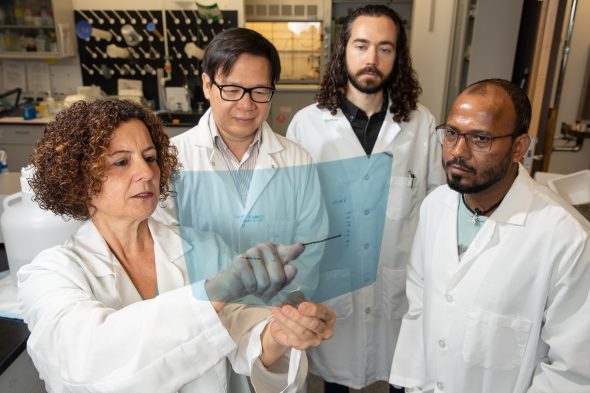

Led by Orly Lazarov, professor of anatomy and cell biology at the UIC College of Medicine, the team found that new neurons can merge with the brain circuits that store memory and recover their normal function.

The results of the team’s study are published in the Journal of Experimental Medicine.

Previous research has shown that neurogenesis, the process of new brain cell production, is inhibited in both Alzheimer’s patients and mice that carry genetic mutations linked to Alzheimer’s. The UIC researchers used genetic engineering to see if they could boost neurogenesis in mice with Alzheimer’s mutations — they deleted the gene Bax, which is related to cell death, in the neurons of the mice. Afterward, testing showed that the altered mice performed better in spatial recognition and contextual memory tasks.

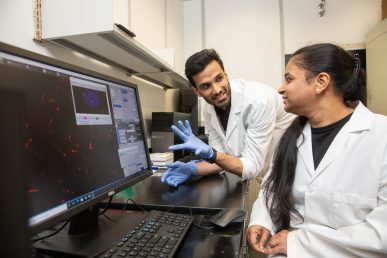

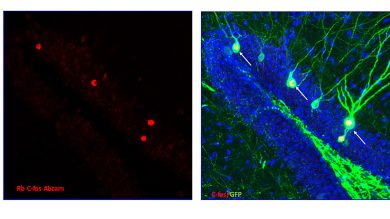

Fluorescent labels that the researchers placed on memory-related neurons in the mice helped them to identify newly formed neurons alongside older, more mature neurons, which contrasted significantly with typical Alzheimer’s mice, which show a lack of new neurons.

Further analysis showed that the treated mice exhibited an increase in dendritic spines, structures in the brain synapses that are critical for memory formation. The gene expression of the mouse neurons also had achieved a more normal profile.

In order to prove the importance of neurogenesis in reversing Alzheimer’s, Lazarov and the team then deactivated the newly formed neurons in the treated mice. This step reversed the improved performance the mice had previously shown in spatial recognition and contextual memory tests.

The researchers say the study could make a big impact in the field of Alzheimer’s disease research. Currently, Alzheimer’s is one of the most expensive diseases in the United States, with costs expected to reach $1 trillion per year by 2050.

“This is the first time that there is evidence that neurogenesis plays an active role in Alzheimer’s disease pathology,” Lazarov said. “Historically, when Alzheimer’s disease was discovered, there was no information about neural stem cells in the brain. It was not known. It is only in the last 40 years that the phenomenon of hippocampal neurogenesis has been established, and only in the last 10 to 15 years that we’ve really looked at the role of those stem cells in the pathology of Alzheimer’s disease. Our discovery really opens up a huge opportunity for new therapies to develop in the field that are based on the enhancement of neurogenesis.”

Lazarov said this work could lead to a whole new spectrum of medications that could restore memory in patients.

Before any neurogenesis-based therapy can be tested in human beings with Alzheimer’s, the results of the UIC team’s findings in mice must be confirmed by numerous duplicate trials, both at UIC and other institutions. Then, Lazarov and her team hope to develop medication or another treatment that can stimulate human brain stem cells to enhance neurogenesis.

Co-authors of the study, titled “Augmenting Neurogenesis Rescues Memory Impairments in Alzheimer’s Disease by Restoring the Memory Stowing Neurons,” include Rachana Mishra, Trongha Phan, Pavan Kumar, Zachery Morrissey, Muskan Gupta, Carolyn Hollands, Aashutosh Shetti, Kyra Lopez, Mark Maienschein-Cline, Hoonkyo Suh and Rene Hen.

Written by Laura Fletcher.