AI, blockchain and phone scans: UIC researchers bring new technology to dentistry

Dentistry is experiencing a quiet but dramatic technological evolution. Many of the advances in artificial intelligence and big data that are changing the way we work, shop and find entertainment may soon make it easier for dentists to personalize care, monitor patients and develop new treatment options.

UIC College of Dentistry researchers are among the first in the country exploring the value of 3D image analysis, data sharing on the blockchain, home monitoring and other clinical technologies. Their perspective is not just to chase the latest hyped tech, but determine how these methods can improve patient outcomes and access to dental and orthodontic care.

UIC dentists and orthodontists often treat patients with rare or complex conditions, including cleft palates, ectodermal dysplasia, craniosynostosis and other complex dentofacial deformities, and provide dental care to traditionally underserved populations. Those activities give an opportunity to develop AI concepts and rigorously test whether they offer meaningful benefits compared with current methods and avoid perpetuating bias.

“It’s a huge advantage to be in an urban area and serve a population that is traditionally disenfranchised and underrepresented,” said Dr. Veerasathpurush Allareddy, the Brodie Craniofacial Chair and professor of orthodontics at UIC. “That means when we train these AI models, we can better adjust for some of the unique factors or challenges these groups of people face and ensure more algorithmic fairness.”

AI for diagnosis, treatment and remote monitoring

Clinicians’ use of radiographs and other scans is essential in determining treatment plans and monitoring patient progress, but repeatedly collecting and analyzing these images is time-intensive for both doctor and patient.

Artificial intelligence offers new approaches for utilizing this important visual data. UIC dentists collaborate with colleagues in the College of Engineering to develop new algorithms for the analysis of these images; for example, determining the amount of growth left in a patient to guide orthodontic treatment. Clinicians currently use a broad four-category scale to measure this development and select between surgery and other interventions, but a new model provides a finer-grained, continuous measurement.

“We applied image analysis, image processing and deep learning methods to estimate the maturity of a patient from spinal X-rays,” said Ahmet Enis Cetin, professor of electrical and computer engineering. “This will be the first step towards a personalized approach to surgery, where AI is used as a new tool to help dentists make decisions.”

A team of dentists and engineers led by Dr. Mohammed Elnagar, assistant professor of orthodontics, also created an AI algorithm that helps select the most effective treatment plan. For instance, the model – trained on 18 years of patient records collected at the College of Dentistry — can judge whether a patient’s treatment objectives would be best met through the use of braces exclusively, or if supplementary surgical procedures are required. Members of the team received Thomas M. Graber Awards of Special Merit from the American Association of Orthodontists for the work.

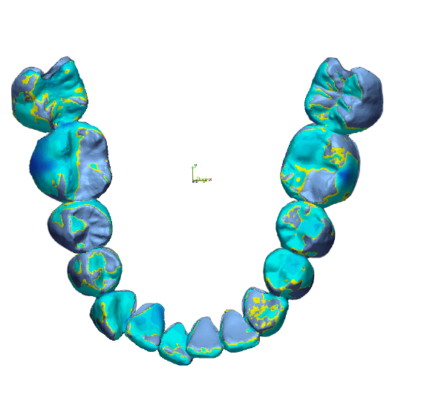

After treatment has started, AI can also help clinicians monitor patient progress, even from afar. For example, patients can use attachments to their smartphone to take their own oral scans at home. An AI algorithm then creates a 3D model that shows how treatment is progressing and identifies potential issues that might require an office visit.

In recent papers, UIC researchers found the quality of these home scans matched what was obtained with regular clinical scans. That equal performance is encouraging for using the technology for early detection of complications. An ongoing clinical trial is testing whether treatment decisions guided by remote monitoring technology are as effective as in-person care.

“You can optimize the patient’s office visits, based on the individual response,” Elnagar said. “If they are responding, they can keep going without a visit. If it moves off track or there is a surprise, we can have them come in earlier.”

The ability to collect high-quality scans at home will also make a meaningful difference for patients living far from clinics or with complicated conditions currently requiring frequent visits.

“It’s really exciting for patients who are limited in their choice of providers,” said Dr. Min Kyeong Lee, a clinical assistant professor of orthodontics who is also studying the ethical considerations of AI applications. “It can save a lot of time traveling, and during the start of some treatments it can sometimes require a visit every month, so it’s a big burden on the family that we can reduce.”

Genomics and the blockchain

While imaging combined with AI can provide powerful data on a patient’s current state, dentists would also like to be able to make accurate predictions about their future. To do so will require additional data, including a rich category that has already made a massive impact in medicine: genomics.

In orthodontics, interventions may last years, and clinicians must anticipate how a patient’s teeth and associated structures will change in order to find the most appropriate treatment option. Genomic information could help dispel that uncertainty and inform decisions, Allareddy said, by identifying associations between certain genes and factors like root resorption and tooth movement.

“We’ll be able to render truly personalized orthodontic care based on the genomic profile of each patient,” Allareddy said. “We can change the treatment or maybe even not do treatment, when the data suggests we would probably be doing more harm than good.”

But dentistry does not have the same access to universal platforms or the culture of data sharing between institutions that exist in medicine. While the UIC College of Dentistry has the advantage of being one of the largest programs in the United States, the types of studies that will unlock the predictive abilities of genetics will require data from much larger patient pools, combined with other modes of information including images and clinical outcomes.

A potential facilitator of these necessary data exchanges could be the blockchain. Though often discussed in the context of cryptocurrency, the blockchain also offers promise as a secure record of information distributed across computers worldwide instead of a single, centralized database.

In a recent paper, Allareddy, Elnagar, Lee and Dr. Maysaa Oubaidin, associate professor of orthodontics, proposed using blockchain technologies to help dental researchers around the world share and learn from clinical data. The system could enable federated machine learning — a form of AI where models are trained on distributed data without moving it from its secure home — and large-scale analyses that unlock the potential of genomic data or test interventions across a broader range of individuals, including those from underserved patient populations.

“If we can really have this huge collaboration between universities, hospitals and clinics and we can focus on organizing the data so everybody can work on one big project together instead of competing, then it may be possible to have no bias or exclusion of minorities,” said Dr. Flavio José Castelli Sanchez, an assistant professor of orthodontics. “We’re trying to eliminate that, and there’s a big chance to do it using artificial intelligence as long as we do it properly.”