Library exhibit highlights Latinx activist ‘Rudy’ Lozano

As a young high school student on the South Side and a college student at the University of Illinois Chicago, Rodolfo “Rudy” Lozano fought for courses on Latin American history and for more Latino faculty.

Lozano’s fight as an undergraduate at UIC led to his arrest with other protestors on the Chicago Circle campus. The struggles they fought would pay off and lead to the creation of the Latin American Recruitment and Educational Services program and the Rafael Cintrón Ortiz Latino Cultural Center.

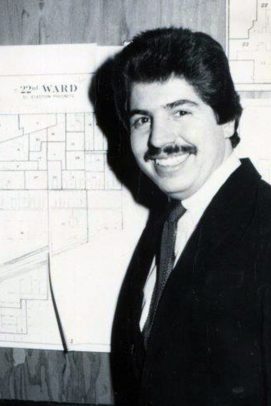

The former activist, community organizer and politician is the subject of a new exhibit at UIC’s Richard J. Daley Library, “A Search for Unity: Rudy Lozano and the Coalition Building in Chicago,” which will run until next fall, said David Greenstein, lecturer in Special Collections and University Archives. The exhibit is made up of papers, photographs, posters and other memories about Lozano, who was murdered when he was 31. Greenstein curated the exhibit with Peggy Glowacki, manuscripts librarian, and Elena Bulgarella, assistant archivist.

“The exhibit focuses on the way he tried to bring different communities of people together,” Greenstein said. “Including various Latinx communities in the Near West Side neighborhoods, Pilsen and Little Village, he brought together documented and undocumented workers that were fighting for better conditions.”

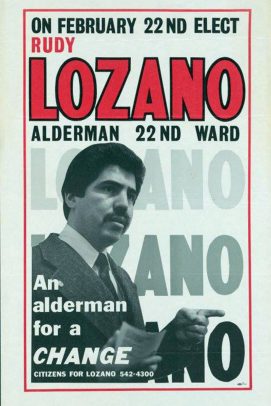

Lozano, who was born in Harlingen, Texas, to Mexican immigrant parents, was gunned down June 8, 1983, after losing a bid to become Chicago’s first Mexican-American alderman. According to news accounts, Lozano failed to force an aldermanic runoff by only 17 votes but managed to get enough Latino voters to support Harold Washington’s successful bid to become Chicago’s first Black mayor.

As a community organizer, Lozano forged coalitions between Black, Latino and white Chicagoans advocating for political change. His history as an activist goes back to when he was a student at the former Harrison Technical High School in South Lawndale, Greenstein said.

He advocated for the school to hire more teachers who were representative of his community and teach Mexican and Latino history because that was what the students were interested in learning, Greenstein said.

When Lozano arrived at UIC, he joined a student movement advocating for the university to recruit more Latino students and reshape the university’s curriculum to teach Latino issues. In addition, they were calling for a cultural center to serve the community on campus. His fight successfully led to LARES and the Latino Cultural Center. Latino students now make up the second-largest group of students on campus.

“For students, especially today, his story is valuable because he began his career so young,” Greenstein said.

After leaving UIC, he worked as a labor organizer with several local groups, including the Midwest Coalition for the Defense of Immigrants, the International Ladies Garment Workers Union and the Center for Autonomous Social Action. As part of his work, he called on unions to advocate for both documented and undocumented workers. He also served to organize workers at the Tortillería Del Rey tortilla factory.

After noting that the time was ripe for the community to back Latino candidates in local elections, he ran for alderman in the 22nd Ward and was a supporter of Washington’s run for mayor. He forged a coalition of Black, Latino and progressive white voters and became an adviser to Washington, who was elected in April 1983. Lozano was expected to serve in Washington’s cabinet but was killed in June by an 18-year-old man he had let into his house to use the bathroom. The circumstances behind the killing remain controversial.

Among the items on exhibit are papers from his union organizing campaigns, including his notes and daily reports during the 1970s. Also included in the 24 boxes of archive materials are posters, photographs and campaign items from his aldermanic campaign, as well as items from Washington’s campaign. Many Washington-related archives show the importance of Lozano’s outreach to the Latino community as being pivotal to the mayoral victory.

The items also include records from UIC’s University Archives that document the creation of the Latino Cultural Center and LARES, as well as items highlighting his campus efforts as a UIC student.

In addition, archivists were able to digitize videos that had not been previously seen, including a 1979 May Day speech, which will now be part of the archives and the exhibit and will be available to researchers. Library officials are digitizing many items to make them available online to the public.

“It’s really exciting because you can see a young, dynamic activist speaking to a large crowd. You get a chance to see how dynamic of a speaker he was,” Greenstein said. “That’s available for the first time on display as part of the exhibit and will be preserved digitally as part of our collections.”

Last year, Cook County officials celebrated Lozano’s legacy by declaring July 29 Rudy Lozano day. He has a Chicago Public Library branch and several schools named in his honor.

Information is available online about COVID-19 guidelines while visiting the library.