Detained youths can’t comprehend immigration documents

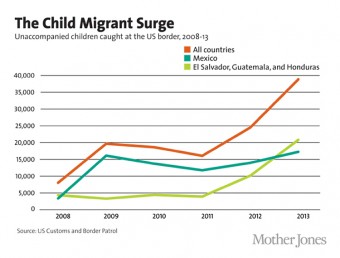

Most unaccompanied, detained immigrant youths cannot read the documents or fully comprehend the processes that drive their immigration cases, according to a new report by education researchers at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

The UIC researchers studied 70 unaccompanied adolescents, mostly from Central America and Mexico, in a Midwest detainment center overseen by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The center receives about 300 children annually, who speak more than 20 languages.

Observations were made over six weeks, and results were compared to the center’s expectations of the youths. Staff at the center were well aware of literacy difficulties. But help from federal agencies was generally limited to translation, which did not always allow the youths to comprehend, the researchers said.

To understand the documents the youths received — either in English or their native language — required a reading level that ranged from ninth grade to college sophomore. The youths’ reading levels in their native languages ranged only from pre-reading to high school, according to residential instructors at the center, with the average being a second- or third-grade level. Most were at a pre-reading level in English.

Due to ineffective communication, many adolescents could not differentiate between legal representatives and advocates, and thus they did not realize how a meeting with lawyers or paralegals could affect their cases.

“Policy makers need to shed more light on the needs of this growing population,” said William Teale, professor of education and director of the UIC Center for Literacy.

“Staff at both the local and federal levels need procedures to help detained youths understand their immigration cases — whether they will be reunited with a sponsor in the U.S., deported to the home country, or taken in by foster care.”

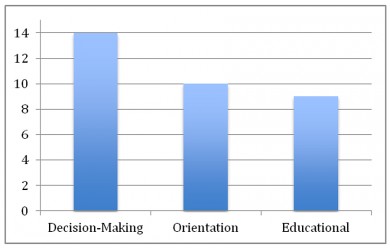

Among the report’s recommendations:

- Revise documents to be more readable, with more illustrations.

- Simplify intake procedures so youths meet fewer people during their first 48 hours in the center, and clarify roles to develop trust.

- Give youths a timeline of necessary events.

- Give youths at least 24 hours’ notice to prepare for high-stakes meetings, and give them a list of frequently asked questions.

- Communicate more effectively about individual cases and conflicting policies between state and federal levels.

“The youths in this secure detainment center are safe, and are being assisted by staff genuinely concerned with helping them achieve their greatest potential, but they need additional advocacy to negotiate the high-stakes literacies that confront them,” said Alexis Cullerton, visiting research specialist at the UIC Center for Literacy and lead author of the report.