Powerhouse proteins protect heart cells from chemotherapy damage

Researchers at the University of Illinois Chicago have identified a process by which enzymes can help prevent heart damage in chemotherapy patients.

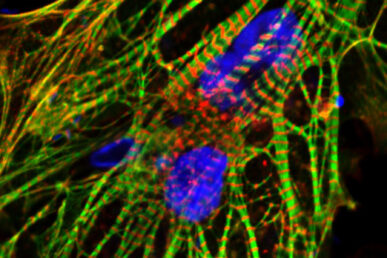

The enzymes are normally found in a cell’s mitochondria, the powerhouse that produces energy. But when heart cells are put under stress from certain types of chemotherapy drugs, the enzymes move into the cell’s nucleus, where they are able to keep the cells alive. The paper is published in Nature Communications.

“As chemotherapy has become more and more effective, we have more and more cancer survivors. But the tragic part is that a lot of these survivors now have problems with heart failure,” explained co-senior author Sang Ging Ong, assistant professor of pharmacology and medicine.

This has led to the rise of a field called cardio-oncology. Most previous research in the field focused on the mechanisms by which chemotherapy drugs damaged the mitochondria of heart cells. This research team was interested in investigating a different angle: Why do some patients’ hearts escape damage? Is there something particular about their cells that is protecting them?

First the team discovered that when the heart cells were stressed by chemotherapy, the mitochondrial enzymes moved into the cell’s nucleus — an unusual phenomenon. But they didn’t know if that movement was the cause of the cell’s damage or the means of its protection, explained Dr. Jalees Rehman, co-senior author, Benjamin Goldberg Professor and head of the UIC Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics.

“We really didn’t know which way it would go,” he said.

To find out, the researchers generated versions of the enzymes that would specifically move into the nucleus and bypass the mitochondria. They discovered that this relocation fortified the cells, keeping them alive. They demonstrated that this process worked in both heart cells generated from human stem cells and in mice exposed to chemotherapy.

“This seems to be a new mechanism by which heart cells can defend themselves against chemotherapy damage,” said Rehman, who is also a member of the University of Illinois Cancer Center.

The discovery suggests new clinical possibilities. Doctors could test individual patients to see if heart cells generated from personalized stem cells would adequately protect themselves from chemotherapy by moving their enzymes from their mitochondria into the cell’s nucleus. Doctors could draw blood from the patient, make stem cells from the blood cells and then use those personalized stem cells to generate heart cells with the same genetic makeup as the patient’s heart cells.

“Assessing the injury caused by chemotherapy and the enzyme movement from the mitochondria into the nucleus of those heart cells in a lab would help determine what the patient’s likely response would be to chemotherapy,” Rehman said.

In patients with inadequate protection, one could then enhance the protection by increasing the enzyme movement and protection of the heart cells.

The researchers are eager to do more studies looking at whether this method could help prevent heart damage from other conditions, such as high blood pressure and heart attacks, and whether it would work in other cells, such as those in blood vessels.

The other authors on the paper are Shubhi Srivastava, Priyanka Gajwani, Jordan Jousma, Hiroe Miyamoto, Youjeong Kwon, Arundhati Jana, Peter Toth and Gege Yan, all at UIC’s College of Medicine. The research was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the American Heart Association.