Cities, suburbs trade and blend design features

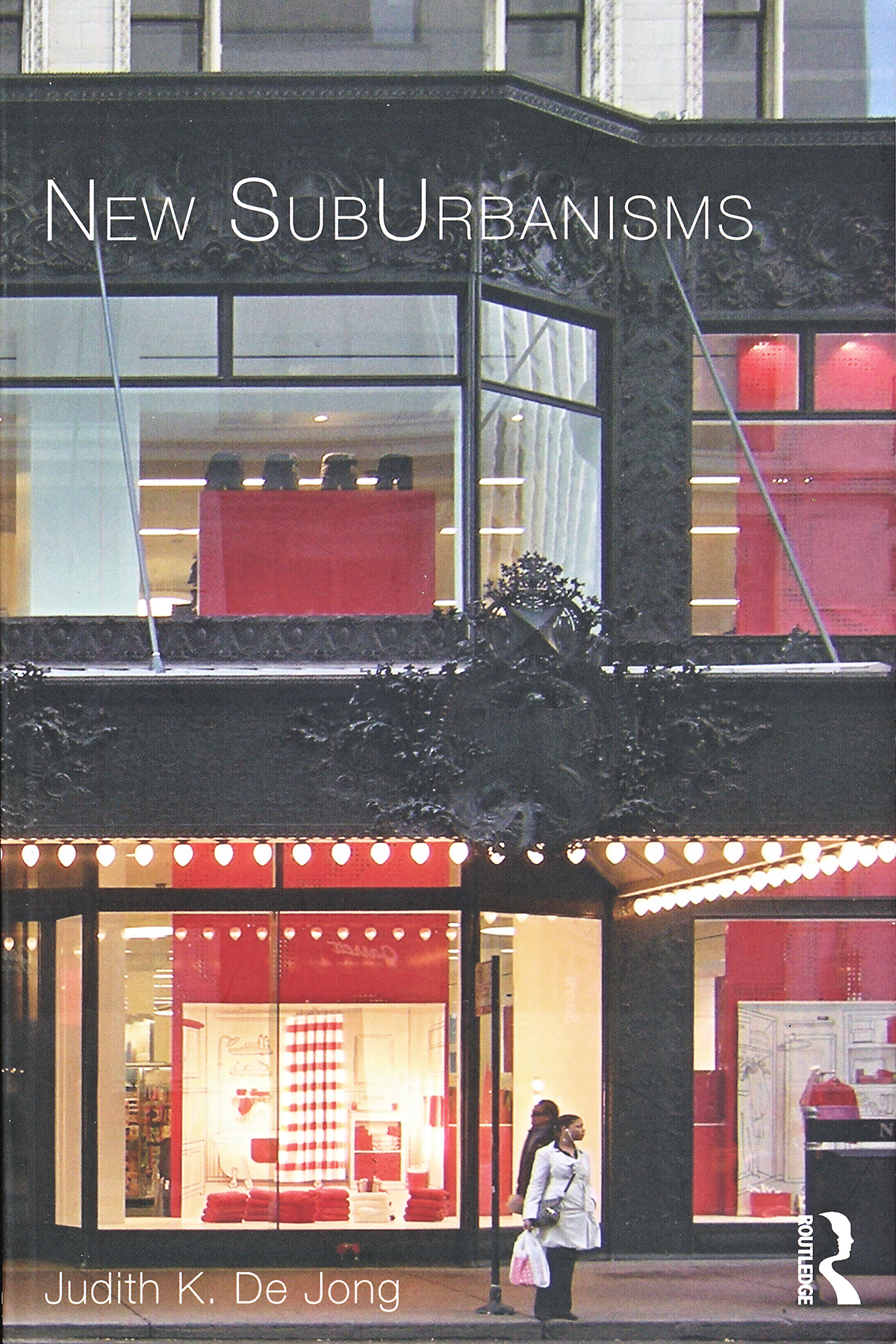

The cover of “SubUrbanisms” features Chicago’s downtown Target store, a suburban big-box concept revised for urban use in a historic building. (Click for larger file.)

Major cities and their suburbs are becoming increasingly alike, but with little acknowledgement or understanding by architects and urban design professionals, says an architecture scholar at the University of Illinois at Chicago in her new book, “New SubUrbanisms.”

Judith K. De Jong, assistant professor of architecture, notes that the post-WWII polarized stereotypes — the city as the dense, diverse, vertical center of business and high culture, and suburbs as the homogeneous, horizontal sprawl of domesticity and mass culture — have resisted revision despite a long history of “urbanizing suburbs and suburbanizing urban cores.”

Ironically, the resulting “flattening” of the American metropolis allows design innovation, because features once considered either urban or suburban can be rearranged anywhere as “sub/urbanisms,” De Jong writes.

She notes that the 20 largest metropolitan areas in the U.S., including Chicago, are all undergoing a similar process, although older cities are changing more slowly. She cites 2010 U.S. Census figures showing that nearly 40 percent of Americans live in those 20 metropolitan areas, making “sub/urbanism” ubiquitous.

De Jong identifies four categories of hybrid suburban/urban space:

Car: In most cities, zoning for off-street commercial parking reflects suburban expectations about convenience and mobility, resulting in oversized parking lots and garages. While some cities are revising these requirements, new designs for parking have emerged, including the parking podium, which integrates a base of structured parking below a residential or office tower, and interstitial parking, which inserts cars into previously underused spaces.

Domestic: Suburbs have added multifamily housing as low-rise townhouses and high-rise apartments, both of which continue to incorporate space for the car. Meanwhile, in changing city neighborhoods, homeowners convert old duplexes and triplexes into single-family houses.

Retail: Big-box stores have been built in cities’ former light-industrial areas and in established neighborhoods, where they usually are designed with multiple floors. Meanwhile, suburban enclosed malls are giving way to open-air “lifestyle centers,” which attempt to combine shopping with urban ways of life, through layouts and traffic patterns that interpret a traditional downtown.

Public: Both cities and suburbs now have highly programmed parks and other public spaces, many of them created through public-private partnerships.

Of the areas where most “sub/urbanisms” arise, De Jong writes: “Since these areas are very much works-in-progress, their current conditions are often ungainly. Consider this a foray that some will challenge, and others will build upon.”

More about the UIC College of Architecture, Design, and the Arts