Developers help fund transit through value-capture plans

Nearby public transportation boosts property values, and increasingly cities are asking developers to help fund transit improvements that will benefit their projects, according to a report by the Urban Transportation Center at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

The most successful “value-capture” policies — by which government agencies recover infrastructure costs through special taxes or voluntary payments from developers — result from bringing developers and taxing bodies together during the earliest stages of transportation planning, the researchers found.

The research team examined various value-capture methods used in four cities operating some of the largest and oldest transit systems in the nation, with the greatest backlogs of unfunded capital needs.

Chicago rapid transit stations

A gubernatorial task force last year found that the Chicago area needed $20 billion in transportation improvements — many in the Chicago Transit Authority.

The researchers studied how tax increment financing districts were used to fund improvements at six CTA elevated train stations. In each of Chicago’s 153 TIF districts, property tax revenue resulting from new development is used for public improvements within that district.

The six stations studied were Morgan on the Green and Pink lines; the Illinois Medical District on the Blue Line; 18th Street on the Orange Line; and Bryn Mawr, Wilson and Harrison on the Red Line.

The value capture to total budget ranged from 2 percent to 100 percent. The researchers concluded that Chicago developers are open to value-capture options, and opportunities exist for transit-specific value capture.

“Rather than use TIF funds, the city should look at transit-specific ways to maximize value capture,” says Jordan Snow, research transportation planner and lead author of the report. “A more distinct set-aside would indicate to developers and the community how valuable the transit station is to neighborhood development.”

New York, Hudson Yards

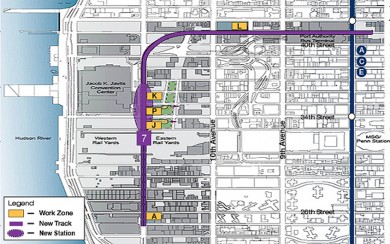

Redevelopment of the 45-block Hudson Yards on the west side of midtown Manhattan prompted New York City to extend the Number 7 subway to the area. The project’s estimated cost was $2.3 billion.

Two planning entities were created: one to control funding and financing, the other to produce the city’s development plan. Rezoning allowed developers to build higher-density buildings at a premium. The resulting funds, plus tax increment financing, will support debt financing.

Establishment of the two planning agencies was an unprecedented way to manage value-capture funding, the UIC researchers found, and the developers’ close cooperation with the New York Metropolitan Transit Authority was critical.

“The Hudson Yards project is a near-ideal case,” Snow said. “Having project- or region-specific corporate entities that are staffed by all stakeholders would be ideal, especially when value capture supports debt payments.”

San Francisco, Parkmerced

Planners sought to add a new station and expand service on the Muni M Line serving San Francisco State University and Parkmerced, a 3,400-unit housing complex being redeveloped.

From 2006 to 2014, more than 500 meetings were held among local and regional governments, Bay Area transit agencies, community and advocacy groups, and the new owners of Parkmerced. Funds for continued study and the new station were secured from community groups and the university.

The project succeeded because transit agencies and city staff cooperated, and because the hundreds of public meetings lent credibility when planners approached the property owner/developer for their contribution, the researchers said.

“We also believe that plan members with a long local history and civic involvement were crucial to the success of the project,” Snow said.

Washington, D.C., NoMa-Gallaudet University

In 1999, the Washington Metropolitan Transit Authority identified the need for a new Red Line station between Union Station and Rhode Island Avenue.

Shortly after announcing the project, the transit agency brought developers, landowners and other stakeholders into the planning process by encouraging them to form an ad hoc, private, civic group. The group, called Action 29, gathered and reviewed development proposals and worked with the transit authority to obtain funding. Action 29 agreed to the creation of a special taxing district that generated $25 million, or roughly one-quarter of the station’s cost.

Since the station opened in 2004, private entities have invested $3 billion nearby in mixed-use development, government offices, and redevelopment of older housing.

“This transit agency has embraced its role as an owner of land assets,” Snow said. “It has hired staff familiar with municipal taxation and with the developer community.”

From the review of case studies, the researchers recommend that:

- transit agencies cultivate proactive staffers experienced in working with taxing authorities and developers

- taxing authorities develop working relationships with the transit agency’s capital planners and station-area development team

- private developers offer feedback to transit systems and understand the value of transit planning to their interests

“Each jurisdiction has unique constituencies, geography, funding variances, fluctuating governmental constraints, opportunities and challenges,” Snow said. “Value capture can be creatively used to structure a funding program that meets local requirements.”