UIC study examines impact of Chicago River reversal on region’s aquatic environments, fauna

Prior to European settlement, wetlands, lakes and streams were the major landscape features of the Chicago region.

Much of this has been altered or lost in the past 150 years, most notably by the reversal of the Chicago River in 1900 with the construction of the Sanitary and Ship Canal. Many animal species that lived in these habitats also disappeared.

Now, a group of graduate students at the University of Illinois at Chicago have quantified over a century of these changes in detail.

In a paper published in the journal Urban Ecosystems, students from the departments of earth and environmental sciences and biological sciences have measured both the extent of wetland loss in Cook County since the time of the river reversal and the alterations in the animal populations. The paper, which is the result of a class project for the course “Extinctions: Modern and Ancient,” compares the changes in aquatic environments and fauna in Cook County during two intervals: 1890-1910 and 1997-2017.

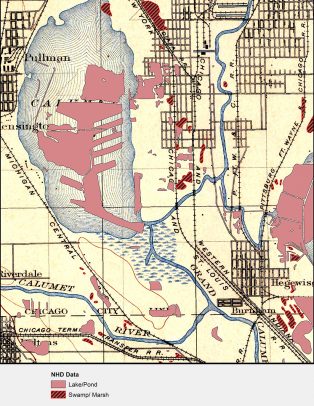

“The areas of aquatic features from historical topographic maps were imported into a GIS database and compared with the modern United States Geological Survey’s National Hydrography Dataset,” said Joey Pasterski, UIC Ph.D. student in earth and environmental sciences and first author of the paper. “It demonstrates the utility of digitized museum collections for long term studies, and it provides further evidence of the uneven impact of urban development on native faunal communities, here specifically in Cook County.”

Digitized maps of the region circa 1900 were used to estimate the area and distribution of wetlands and lakes for comparison with current patterns.

According to the researchers, the area of wetlands has decreased by more than 80%, with many of these being drained or converted into small and relatively isolated lakes and ponds. The remaining wetlands are also small and fragmented.

Museum records and natural history surveys from sources such as the Field Museum and the Chicago Academy of Sciences allowed them to reconstruct the historic existence of species in the wetlands and lakes for comparison with modern data.

The researchers found that 23 species of fish, 54 species of clams and snails, and three species of reptiles have disappeared locally. There also are many new invasive species.

All 25 aquatic birds reported from the 1890-1910 period still exist and an additional 13 have been reported in recent times. Increased observations by birders are cited as the potential factor for the number of new bird species recorded.

The students hope the study can help inform the direction of future research aimed at restoring the health of aquatic ecosystems within Cook County and elsewhere.

“This could spawn a series of similar studies to help improve the accuracy of our understanding of the long-term effects of urbanization on native communities across the world in varying climates, environments, and urban systems, with the expressed goal of improving the health of urban ecosystems,” Pasterski said.

The Chicago region provides a case study of the impact of human landscape change on regional animal and plant life, notes Roy Plotnick, UIC professor of earth and environmental sciences.

“We err in thinking global change is just global warming. On all scales, humans have profoundly changed their environment,” said Plotnick, who supervised the study and is senior author of the paper.

Other UIC student authors of the paper are Anthony Bellagamba, Stephanie Chancellor, Alister Cunje, Emily Dodd, Kerri Gefeke, Shannon Hsieh, Alec Schassburger, Alexis Smith and Wesley Tucker.